Open Educational Resources (OER) are materials used to support education that may be freely accessed, reused, modified and shared by anyone. OER include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, research articles, videos, and other materials used to support education. OER creators own the intellectual property and copyrights of the OER they create. However, they license the OER and make it freely available to others.

Every time I present the OER work I do at BCcampus I face questions from the audience:

- “Why would a creator who holds copyright and intellectual property license it for others to freely access, reuse and modify for their own purpose?”

- “Why would a creator give something away for free when it has inherent potential to generate revenue and income?”

- “How does a creator earn a living giving away their work for free?”

- “Why would an institution that relies on grants and student fees make core assets freely available to others?”

- “Given the dire financial times countries, governments, and public education providers find themselves in why would we adopt this practice of open?”

- “What is the business model of open?”

To those questions another one was added when David Porter and I were in Ottawa presenting the work of BCcampus broadly including the benefits of Open Educational Resources to Canada’s federal government.

The question we got asked there that stuck out for me is:

“How does open not only save money but act as an economic driver?”

The UNESCO / Commonwealth of Learning project Fostering Governmental Support for Open Educational Resources Internationally led by Sir John Daniel of the Commonwealth of Learning and Stamenka Uvalic-Trumbic is hosting a series of regional policy forums on OER for governments between now and the World OER Congress in June 2012. The purpose of these policy forums is to raise governments’ awareness of OER and their support for them, as well as getting input to the Declaration on OER and Open Licensing that will be put to the June OER Congress.

Shortly after returning from Ottawa Cable Green of Creative Commons sent out a request for responses to a question coming out of these policy forums:

“What is the business case for OER?”

I like all these questions.

Open needs to make financial and economic sense.

All of us involved in OER work need to be able to answer these questions directly.

We need to be able to state in simple, straightforward terms the economics of open.

So that got me to thinking that I should tackle these questions.

Someone needs to make a stab at generating answers.

So here goes.

Cable Green’s request for input into what the business case for OER is generated a flurry of responses and recommended readings on international OER list servs. I’ve gathered those readings into a What is the business case for OER? Collection which I’ve pasted at the end of this blog post. In addition my colleague Scott Leslie began assembling evidence of the economic benefits of many different kinds of open including open access research publishing, open source software, open standards, open data, and OER. I spent some time going through all these resources seeking to extract short straightforward statements that answer the question, “What is the business case for OER?” Here’s what I came up with.

OERs:

- increase access to education

- provide students with an opportunity to assess and plan their education choices

- showcase an institution’s intellectual outputs, promote it’s profile, and attract students

- convert students exploring options into fee paying enrollments

- accelerate learning by providing educational resources for just-in-time, direct, informal use by both students and self-directed learners

- add value to knowledge production

- reduce faculty preparation time

- generate cost savings – (this case has been particularly substantiated for open textbooks)

- enhance quality

- generate innovation through collaboration

The business case for OER includes both cost savings and revenue generation. Making something open is not always a means of direct revenue generation. It often is indirect – because something is open it leads to a revenue opportunity that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. Using OER as a means to market reputation and institutional prowess can convince students to enroll. While better quality learning resources may not directly generate revenue they can lead to faster learning, greater learner success, or reduce drop outs. By their very nature OER can lead to new ways of education through more cooperation, collaboration, and partnerships between institutions. OER make totally new forms of education possible and bring new players into the education market.

I expect many of you may have additional short straightforward statements that answer the question, “What is the business case for OER?”. Welcome your statements as comments to this blog. I expect many more elements of the business case to emerge as the practice of open in education matures.

While the above statements provide a business case for OER they don’t completely answer questions associated with financial rewards to creators who share, or the business models of open, or how open acts as an economic driver. With the business case established lets move on to defining these other economic aspects of open.

The economics of open can be described from multiple perspectives. If I am a creator I describe it one way. If I’m a consumer I describe it another.

In education the way I describe the economics associated with open differs depending on whether I”m describing it from the perspective of a student, an instructor, a college, the education system of a region, or government of a nation.

The economics of open also differ depending on whether you are taking a public or private perspective. Education is both a public service and a for-profit activity around the world. In the public service context there is a very strong business case that publicly funded goods be made freely available to the public that funded them.

In the current OER higher education context “creators” are faculty and/or institutions. When you look at a question like “How does a creator earn a living giving away their work for free?”, in a public sector context the answer is partly that those in the public sector are already earning a living via salary derived from public taxpayer dollars. If they are already being paid by the public shouldn’t the educational work they are being paid to develop, whether it be research or educational resources, be freely available to the public?

After thinking a lot about which persona I should describe the economics of open for and which sector, public or private, I decided to discard these differentiations and focus in on how the economics of open generates benefits that accrue to all players regardless of who you are and regardless of whether it be for public service or for profit. My aspiration is for short direct answers that make sense to everyone.

To derive answers I started looking at things like open source software business models, the sharing economy, and how digitization and the Internet affect supply and demand. There is a lot to explore! I’ve taken it on as my challenge to show how the economics of open, as it plays out in other sectors, applies equally well to education. The language of business and economics is not always used in education. However, for the purpose of generating direct short answers that everyone understands I have chosen to use the language of business and economics in my answers.

Here then are my answers.

Open enables rapid market entry, market penetration, and market share.

We are all creators. Some take photos, some make music, some paint, some write. Most creators are interested in having others experience their work. However default copyright and IP laws tend to constrain access, dissemination and use. Openly licensing work reduces barriers to access and dissemination friction. Going open is a good way to make the market aware that you exist. When something is open it can be disseminated quickly and widely to people everywhere. You may have created a great work but if no one knows about it then its not generating you, or anyone else value.

A central reason for developing and distributing free open source software is that it enables fast entry into the market, rapid market penetration, and generates market share. When Google made the source code for Android open they wanted to make sure that there would always be an open platform available for carriers, OEMs, and developers to use to make their innovative ideas a reality. They also wanted to make sure that there was no central point of failure, so that no single industry player could restrict or control the innovations of any other. The single most important goal of the Android Open-Source Project (AOSP) is to make sure that the open-source Android software is implemented as widely and compatibly as possible, to everyone’s benefit.

Educational institutions who go open frequently report institutional impact in marketing terms.

Patrick McAndrew at the UK Open University in 2009 reported in his Learning from OpenLearn presentation that the the institutional impact from their OpenLearn initiative included:

- 3 million new “users”

- 232 countries

- 7700 “sign ups”

- 10 funded projects

- 30 collaborations

- established methods

- changed image

- won awards

- new plans

In October 2011 BBC News reported Open University’s record iTunesU downloads had reached 40 million and put the Open University alongside Stanford University for the most downloads.

In 2011 after ten years of open sharing, MIT states it shared its OCW materials with an estimated 100 million individuals from over 200 countries worldwide. MIT’s goal for the next decade is to increase their reach to a billion minds.

The UK Open University, MIT, and Stanford all get that going open enables rapid market entry, market penetration, and market share. They’ve established first mover advantage in building up their market presence. For them going open is good business.

As the OER field moves forward I expect we’ll see data that shows increased enrollments where OER exists for courses and shows conversion benefits associated with students being able to try before they buy.

Open generates revenue through advertising, subscriptions, memberships, and donations.

When most people hear about open they find it hard to imagine how making something you own, open and free to others could possibly yield a financial benefit. Obviously you’re not going to generate direct revenue from a free resource. However, you can generate indirect revenue and there are lots of existing business models that already do so which education can emulate.

Advertising

Google makes a search engine available to all Internet users for free. It makes its revenue from advertising.

Facebook provides a free social network platform that supports personal networks, friendships, and social movements. It makes its revenue from advertising.

Given the market valuations for Google and Facebook it’s clear that the business model of generating revenue from making something you own, open and free to others can generate large financial benefits from advertising. Both Google and Facebook have worked hard to make the advertising tolerable by personalizing and targeting it to match your interests and needs as closely as possible.

Advertising and education tend not to mix. There is a tacit understanding that education should be pure and not unduly influenced by something so crass as advertising. However, given the success of ventures like Google and Facebook I expect this will change. Already sites like Udemy have emerged. Udemy’s goal is to disrupt and democratize the world of education by enabling anyone to teach and learn online. They’ve built a platform that makes it easy for anyone to build an online course using video, PowerPoint, PDFs, audio, zip files and live elements. Students can take courses across a breadth of categories, including: business & entrepreneurship, academics, the arts, health & fitness, language, music, technology, games, and more. Most courses on Udemy are free, but some are paid. Paid courses typically range in price from $5 – $250. Udemy features advertising in their third column (aka Facebook) and takes a percentage of each course fee.

Its important to point out that sites like Google, Facebook and Udemy are not open in the full sense that I established at the beginning of this blog. Open in its fullest sense means education resources that are freely accessed, reused, modified and shared by anyone. While Udemy provides “free” access everything on the site is locked down by copyright and can not be reused or modified.

Subscriptions

My own blog, EdTech Frontier, is built using WordPress open source software. Anyone can create a blog for free at WordPress.com. You get a whole array of free functionality – customizable design themes, ability to write posts, upload and embed photos and videos, stats dashboard, privacy options, complete hosting, … This free functionality is sufficient to get you going and may be all that you need. But for those who want more control you can subscribe to premium features. WordPress generates revenue from advertising so if you don’t want advertising you can remove ads from your blog for a low yearly subscription fee. Think about that for a minute – if its free you accept advertising, if you don’t want advertising you pay a fee. Additional subscriptions get you your own domain, extra storage, custom design, VideoPress, … The business model is very clear – basic for free, premium for a fee.

GoodSemester is an education platform that has adopted the same subscription model. GoodSemester is interesting in that it has been developed by students. They think that education deserves the collaborative power and ubiquity of the Internet, and they don’t understand how schools have gotten on for so long without some amazing tools we take for granted in other fields. GoodSemester is a course platform for students and teachers providing a means for developing and delivering online courses, notes, assignments, questions, discussions, groups and analytics. GoodSemester offers subscription plans for students and professors. While not exactly “free” GoodSemester is interesting for the way it has adopted business models from open source software entities like WordPress and applied them to education.

Memberhsips and Donations

Open initiatives like Wikipedia and Creative Commons are committed to the ideal of free and open with no restriction or influence from prospective advertisers. Accepting donations provides them with the independence they need to achieve their mission. Curriki the online community and wiki platform for teachers, learners, and education experts to share, reuse, and remix free quality K12 curricula uses both donations and memberships as a means of financing its work. Curriki membership is free to educators, but they ask a small annual membership fee from individuals who join Curriki representing for-profit entities. In exchange for a small annual membership fee, you can publish the Curriki logo on your Web site and let the world know you are a corporate member! Donations are welcome from anyone.

Open generates revenue through services.

Proprietary off-the-shelf software is funded through the sale of licenses to end users. Open-source software is given away for no charge. One of the main funding mechanisms for open source software is ancillary support services. Revenue is generated by value added resellers and integrators who specialize in supporting open. Consulting, selection of open source software, installation, configuration, integration, training, maintenance, customizing and tech support are examples of services used to generate revenue from open. The software is free but these fee-based services enable users to optimize use of the product and extract value from it. Its worth pointing out that proprietary off-the-shelf software often requires these support services too, so open source software typically provides a lower cost solution by not charging a license fee for the software itself.

Linux, Apache, Drupal, MySQL, MediaWiki, the list goes on and on of open source software available for free but whose full utilization is best achieved through support services. Red Hat provides services for Linux. O’Reilly Media has built a business around providing books, magazines, research, and training for open source software. Pick your open source software product and inevitably there is a local or global business providing support services for it.

There are a growing number of open source software applications in education. Moodle, Sakai, and recently Pearson entered the fray with OpenClass. As might be expected there are revenue generating business models around each of these.

Moodle has the Moodle Service Network. and here’s how Pearson promotes its product:

OpenClass has no hardware costs, licensing costs, or hosting costs. Why would we do that? Because “free” enables the widespread adoption of new learning approaches that encourage interaction within the classroom and around the world. OpenClass is unbelievably easy to set up. It works with what you’re already using. Get set up with just a few clicks and instantly import content from other learning management systems such as Blackboard, Angel, or Moodle. OpenClass is simple to install, simple to use, and simple to support. We’ve provided a robust KnowledgeBase, up-to-date support forums, and numerous demos and instructional videos to help you get the most out of OpenClass. Of course, we know that self-service isn’t the right solution for everyone — we also provide 24/7 email, phone, and chat support to instructors, students, and administrators. (emphasis added by me)

The OERu is a more fascinating model. As described on its home page:

The OER university is a virtual collaboration of like-minded institutions committed to creating flexible pathways for OER learners to gain formal academic credit. The OER university aims to provide free learning to all students worldwide using OER learning materials with pathways to gain credible qualifications from recognised education institutions. It is rooted in the community service and outreach mission to develop a parallel learning universe to augment and add value to traditional delivery systems in post-secondary education. Through the community service mission of participating institutions we will open pathways for OER learners to earn formal academic credit and pay reduced fees for assessment and credit.

In each of these examples open has a fee for services built around it. Eric Raymond, in his book The Cathedral and the Bazaar called this “Give Away the Recipe, Open A Restaurant.”

Almost all the early examples of Open Educational Resource initiatives – MIT OpenCourseWare, Connexions, Carnegie Mellon Open Learning Initiative, UK Open University’s Open Learn, and even the new initiatives like MITx are based on a model I think of as “Content for free, Teaching & Credentialing for a fee”. Explicit in all of these OER initiatives is that contact with faculty and the actual credential or degree that is awarded are not part of the offer. Those are services that cost.

The OERu is looking at a business model where some teaching/tutoring services are provided through academic volunteers international see A Framework for Academic Volunteers International: Dec 5-16, 2011. In the absence of teaching services and faculty contact students will turn to each other through initiatives like OpenStudy. I personally see a tremendous opportunity around bolstering education globally through OpenStudy student to student peer mentoring and support.

Teaching and credentialing are two areas of service that are undergoing change in the open market. Institutions like MIT and Stanford have brand value. A credential from those institutions has cachet. Indeed all institutions tend to think of themselves as having a prestigious brand. In the open market brand prestige and its value is undergoing change.

Udacity is co-founded by Sebastian Thrun one of the Stanford University professors who co-taught the massively open Artificial Intelligence course last year that attracted over 160,000 students from more than 190 countries. After teaching this course Thrun left Stanford to found Udacity believing that university-level education can be both high quality and low cost. Udacity aims to use the economics of the Internet, to connect some of the greatest teachers to hundreds of thousands of students in almost every country on Earth. Currently Udacity has investment funding and is offering its courses for free while it figures out its business model with several possibilities for revenue generation described in the article Massive Courses, Sans Stanford. Thrun is leveraging brand value out of his own name rather than Stanford’s.

This idea that students will accept and appreciate a credential not from an institution but from a teacher has been done before in Massively Open Onlne Courses and is now emerging in the form of badges. The MITx initiative has put a new spin on this by devising a credential not exactly from MIT but associated with MIT. The extent to which these badges, letters and certificates of completion from an instructor or non-traditional institution have credibility and value in the market will be fascinating to see.

Open generates revenue through direct and indirect sales

In the economics of open there still are direct and indirect sales. Participants who receive free and open educational resources may still pay for teaching, assessment, and credentialing. The open textbooks being generated in the Washington States Open Course Library initiative aren’t completely free merely targeted to be less than $30 compared to $100-200. Open textbooks are often free in a .epub or .pdf format but cost for a physical print version. I think of this as “Digital for free, physical for a fee”. FlatWorld Knowledge, CK12 and others have all created an open business model around this new way of generating textbooks. The traditional print industry is scrambling to adapt. The economics of open still generates revenues but equally importantly generates cost savings. Take a look at the OpenStax Student Savings Calculator to see how big an impact this can have.

It has been fascinating to see Reuven Carlyle and Cable Green work together to establish the business case for open textbooks and create government policy that leverages the economics of open for Washington State. (Reuven Carlyle makes the business case here. Cable Green makes the business case here.) When you amplify cost savings at a state or national level the economics of open impact is huge.

Another variation on the digital for free, physical for a fee model, is software for free, hardware for a fee. In the rapid market entry section of this post I described why Google made the source code for Android open. Google’s end game was to generate revenue through direct sales, not of software but of hardware in the form of the Android phone itself. Lets see how well this tactic worked. As of February 2012 there were more than 400,000 apps available for Android, and the estimated number of applications downloaded from the Android Market as of December 2011 exceeded 10 billion. Android is one of the best-selling smartphone platform worldwide with over 300 million Android devices in use by February 2012. According to Google’s Andy Rubin, as of February 2012 there are over 850,000 Android devices activated every day. I’d say this strategy works pretty well. Eric Raymond, in his book The Cathedral and the Bazaar called this “widget frosting.” To date we’ve not seen hardware specifically designed and developed for the education market. But I see it coming and I bet it follows a similar model.

Another way of generating direct and indirect revenue from open is to build product add-on extensions and accessories. In the case of add-on extensions the base product is open and free, but additional more full-featured functionality costs money. Lots of apps work this way. You can download a basic app from Apple or Google but an “upgrade” is available for a fee that provides a more robust and full-featured version of that app. Product extensions can be modules, plug-ins or add-ons to an open source package. Indirect revenue can be achieved through accessories which provide users with an opportunity to customize something open in a way uniquely personal to them. The accessories market is huge. Ringtones, laptop covers, apparel, mugs, cards, the variety and range of accessories is endless.

It’s worth pointing out that in music, book, and photography markets some creators give their work away for free and simultaneously offer it for sale. Nine Inch Nails have a brand new 36 track instrumental collection called Ghosts I – IV. You can download the first 9 tracks for free. You can get all 36 track in a variety of digital formats for $5. You can get the tracks on two audio CDs for $10. You can get a a deluxe edition package which includes a blu-ray disc with the songs in high definition stereo and accompanying slideshow. You can get a $300 ultra-deluxe limited edition package (already sold out).

Giving away songs for free can generate more sales.

Cory Doctorow is an author who lets you download his books for free or buy them. He provides a great explanation on why he does this.

Open Generates Innovation

What makes open different is not so much what it derives economic returns from, but “how” it does so.

Open disaggregates supply chains into constituent parts and makes one or more of those parts open and free.

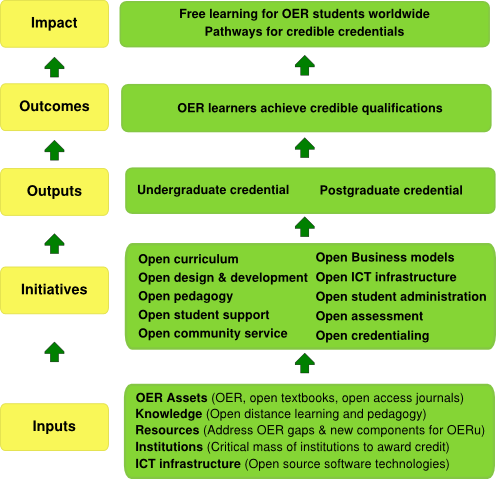

Here’s the OERu logic model:

Although it wasn’t designed for this you can see education supply chain parts revealed – textbooks, journals, curriculum, design & development, pedagogy, student support, ICT infrastructure, assessment, credentialing, … The OERu is looking at how open makes one or more of those parts free or substantially lower in cost.

Open diversifies and democratizes both the production and use of goods and services.

The innovation around open is not based on hoarding knowledge or building monopolies and locked-in proprietary models but instead on freeing knowledge, building collaborations, and finding flexible shared ways of generating economic benefits.

If I give you something and you give me back a new and improved version of that thing, we have engaged in mutual exchange. There has been no financial transaction but we both have mutually benefited. If we have a shared educational need, lets say we have common curricula across a range of courses. Using the economics of open we can divvy up the effort associated with creating that curricula and openly license the curricula for mutual use.

One of the ways the economics of open drives the economy is through reciprocity – by granting you rights I too gain.

Innovation is an economic driver. While the business case for open can be made within traditional frameworks its greatest impact is felt through new business models. When representatives in Canada’s federal government ask me how open acts as an economic driver I’m tempted to ask in reply, “How important the digital economy is to Canada?”

While the business model of open can work with physical goods, its effect as an economic driver is compounded when digital goods are involved. The economics of physical goods is predicated on supply and demand. If I have a physical good and I give it to you, I no longer have it. However, if I have a digital good and I give it to you, I still have it. This fundamentally changes the economics of supply and demand.

In a traditional economy based on supply and demand, scarcity generates premium prices. Supply emphasizes mass produced solutions that are just good enough to attract a large segment of users without being optimized for anyone. The power of the marketplace lies more with suppliers than customers. In contrast, the open marketplace, especially the digital open marketplace, massively diversifies and expands supply. In the open marketplace we all become suppliers and power shifts toward customers.

The open market reduces supplier lock-in and offers lower costs, more choice, and personalization options.

In the open marketplace you can choose what best meets your needs, customize the solution to a much greater extent, and flexibly integrate pieces into more complete solutions.

One of the greatest innovations in the open economy is the formation of communities of developers and users who collectively work on and continually enhance creative work for mutual benefit. So when I see Washington state developing an open course library of their top 81 high enrollment courses and a series of <$30 open textbooks I think about how this could scale by working with other states and regions. I think about the formation of an open consortia of others who collectively use the same courses and improve them together. I think about coordinating and building out through collectively planning and distributed effort.

Almost all successful open initiatives have a vibrant and active community built up around them. An intriguing innovative aspect of this is that frequently the community that forms around open is global not regional.

Leveraging open as an economic driver involves developing and delivering open products and services in partnership with others around the world.

Open leads to collaborations and trading partners within a global context.

Open Makes Better Use of What We Already Have

As I’ve thought about and worked through the economics of open in this blog post its occurred to me that the biggest opportunity open brings to all of us is making better use of what we already have. We are all creators. What if we adopted a default of sharing instead of not sharing?

On January 24-26, 2012, one hundred thought leaders from all over the world were invited to come together in Austin to mark the tenth anniversary of the NMC Horizon Project. They engaged in discussions around ideas of where technology is going and how it is impacting learning and education worldwide. From those discussions megatrends emerged. A number of those trends directly relate to the economics of open including:

Openness — concepts like open content, open data, and open resources, along with notions of transparency and easy access to data and information — is moving from a trend to a value for much of the world.

- The world of work is increasingly global and increasingly collaborative.

- The Internet is becoming a global mobile network — and already is at its edges.

- Legal notions of ownership and privacy lag behind the practices common in society.

- Business models across the education ecosystem are changing.

At BCcampus we’re committed to being open in everything we do. We decided to proactively state that position and openly share the work we produce through a corporate statement on our “open agenda”. It starts out saying:

We are a publicly-funded organization serving British Columbia’s post-secondary sector. The goal of higher education is the creation, dissemination, and preservation of knowledge, and as such we have an essential responsibility to distribute the results of our work as widely as possible.

Our open agenda corporate statement goes on to describe our commitment to publishing all BCcampus reports, web content, and other media resources using Creative Commons licenses. We describe how our events will be open and use open communication practices. At BCcampus open is a default practice. We belief there is collective value in proactively publishing organizational statements regarding committment to open. We hope more organizations follow suit and welcome others to adopt or use ours as a starting point.

In Mark Zuckerberg’s masterplan for the ‘sharing economy’ the CEO of Facebook believes he is not changing human nature but enabling it. Zuck’s Law decrees that every year, we will share twice as much as we shared the year before, because we want to and because we now can.

I’m fascinated by the emergence of the sharing economy. As Fast Company notes in their article on The Sharing Economy:

Spawned by a confluence of the economic crisis, environmental concerns, and the maturation of the social web, an entirely new generation of businesses is popping up. They enable the sharing of cars, clothes, couches, apartments, tools, meals, and even skills. The basic characteristic of these you-name-it sharing marketplaces is that they extract value out of the stuff we already have. The central conceit of collaborative consumption is simple: Access to goods and skills is more important than ownership of them. Botsman divides this world into three neat buckets: first, product-service systems that facilitate the sharing or renting of a product (i.e., car sharing); second, redistribution markets, which enable the re-ownership of a product (i.e., Craigslist); and third, collaborative lifestyles in which assets and skills can be shared (i.e., coworking spaces). The benefits are hard to argue — lower costs, less waste, and the creation of global communities with neighborly values.

Making better use of what we already have generates economic benefit by increasing utilization.

Given the worldwide demand for education shouldn’t we be doing a better job of using what we already have? Don’t the principles we see at play in the sharing economy apply equally well to education? If we really want to address the world wide shortage of education an obvious first step is to open up the education resources that already exist within education institutions around the world.

The economics of open drives the economy through better utilization of what we already have.

Economic development is driven by skilled labour. Better use of existing educational resources increases access and skill development. The economics are simple.

The economics of open allows us to increase the skills and knowledge of all.

Too many of our educational resources sit on a shelf unused or behind password protected systems. Open makes better use of what we already have.

Open works don’t end, they expand and evolve on and on through others.

This post is for everyone who has been grappling with the business case for open.

My hope is that you’ve had a few “aha” moments and that some of your questions have been answered.

I expect many of you have additional insights and examples of the economics of open.

I invite you to share your insights and examples by leaving comments at the bottom of this post.

The more we can collectively expand and evolve a global understanding of the economics of open the better for all.

Reprinted under Creative Commons license from Paul’s blog: edtechfrontier.com

You will also find there references for What is the business case for OER? Collection (from OER list serv Feb 2012)

Written for Open Education Week March 5-10, 2012