Since the British Columbia government announced an Open Textbook project October 16, we have fielded many questions about it. This is Part 3 of our attempt to provide the basic information on Open Textbooks and the project itself, and the questions came from Tony Bates. He recently published the answers on his web site, but we’re also publishing our answers (provided by David Porter) here, some of which expand on the answers already given in prevous posts in this series.

If new texts are being created, will they incorporate web features, such as video-clips, student activities, hyperlinks to other web materials, etc. or will they be mainly a digital version of a printed textbook?

If new texts are being created, will they incorporate web features, such as video-clips, student activities, hyperlinks to other web materials, etc. or will they be mainly a digital version of a printed textbook?

We are aiming to incorporate web features, multimedia links, etc. With the adoption, adaptation and development potential in the open space, this may be the perfect time to bring together other forms of open resources such as simulations, lab materials, video materials and other web materials into the mix as we build a larger open architecture for learning. We already have a 10-year repository of OER from which to draw material, SOLR, that could be incorporated into open texts.

In addition, many print textbook publishers provide sets of study questions and multimedia learning resources online and we intend to replicate that practice where it’s pedagogically appropriate. While textbooks may be only one form of open resource, they are still a major component of the academic ecosystem. The open textbook program in British Columbia provides us a launch pad in which to consider a more integrated approach to bringing all open educational resources into play.

It’s one thing to create the textbooks; it’s another to get faculty to agree to recommend them to students. What incentives will there be to encourage faculty to adopt these open textbooks in their courses?

Clearly faculty and instructors are key players in that they assign textbooks. I would suggest that students have a big voice here, too. In particular, if a peer-reviewed open textbook resource is evaluated to be as good as a conventional publisher resource, why not use it? Especially given the customization and flexibility of open-licensed materials available both to students and instructors.

That said, we do expect to be providing stipends for faculty and instructors to review open textbooks and to consider them for adoption or adaptation. We need to engage with articulation committees as well. Some deans and instructors have already signaled their support for the idea, their willingness to test out some of the proposed open materials and to recommend others they’ve identified.

The funding we receive will be used to support all of the components of building an open resource program including: awareness building, training, implementing review mechanisms and adopt-adapt-develop processes, tools and infrastructure to author, manage and distribute open materials.

Have you been talking to publishers about this plan? If so, what has been their response?

We have been proactively approached by a number of publishers and publishing entities to talk about the open textbook program. In some cases, these have been publishers with existing open materials they would like B.C. educators to consider. In other cases they are textbook publishers who are seeking to better understand how they could become involved.

There are also publishers who have technology and infrastructure services that could be important to us. We were a pioneer user of Pearson Education’s Equella digital repository software to create SOL*R, B.C.’s first open education repository. We are currently using http://pressbooks.com as an environment in which to develop five pilot open textbooks for an information-technology program. That pilot program had been requested by northern B.C. institutions, and pre-dates the bigger open textbook announcement.

It’s our intention to keep the public, including publishers, fully informed about our progress through our corporate web site and our Opening Education site.

What impact will Open Textbooks have on revenue from campus bookstores?

We don’t expect this project to have much impact on bookstore sales, given the scope of the project (40 courses compared to hundreds or thousands in some institutions). We welcome input to this project from all stakeholders, including campus bookstores, and will be actively seeking collaboration from a wide cross section of the B.C. post-secondary system.

What protections or benefits will there be for authors or subject matter experts who participate in the creation or adaptation of these open textbooks? I’m presuming they will have a Creative Commons license, but is there anything beyond that, such as royalties or other benefits? If not, why would they do it?

Authors or subject matter experts who participate in the creation or adaptation of open textbooks will be compensated for their efforts. We have used agreements with institutions in past to fund development including release time and other stipends for developers. We expect to use the Creative Commons license model that allows authors and developers to extend reuse rights for works they author or develop.

Is BCcampus getting any extra funding from government for this initiative? If not how will any costs be covered?

BCcampus has traditionally managed the Online Program Development Fund (OPDF) for the British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Education, Innovation and Technology. The annual fund has been on average $750K – $1M. This fund has supported the development of online courseware, lab materials, online tools, video and other resources over the past 10 years. It is our expectation that OPDF funds will be re-profiled to focus on the open textbook program.

You mention on the BCcampus website that this project is modeled after the recent California legislation. Does this mean that the provincial government has passed legislation for this to happen? Can you explain what the California legislation does?

Unlike California, the B.C. provincial government has not passed legislation. Our approach is modeled on the key elements of the California legislation that we believe could also work in a British Columbia context. The things we liked about the California legislation that we will try to emulate include:

- Free access to textbooks in the most highly enrolled first and second year post-secondary courses.

- Government funding to create a library of free textbooks for students and faculty.

- Open-licensed, to ensure faculty can utilize their skills to remix, revise and repurpose these textbooks for their students.

- Courses and textbooks overseen by the establishment of the “California Open Education Resources Council” (COERC). We’ll establish a similar group.

- California Open Source Digital Library to house the open source textbooks and courseware. We’ll use our own digital library currently in place.

- Call for proposals process for faculty, publishers, and others to develop open digital textbooks and related courseware.

- All materials to be reviewed for quality

—

See also:

- Questions and Answers about Open Textbooks, part 1.

- Questions and Answers about Open Textbooks, part 2.

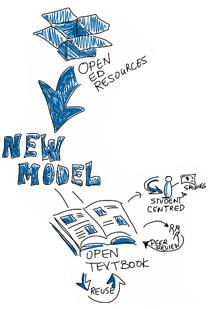

Image derived from a graphic created by Giulia Forsythe and remixed/re-used under Creative Commons license.