The following is a transcript of Amanda Coolidge’s keynote for the Open Education 2019 Conference in Phoenix, Arizona, on November 1, 2019.

In Canada we are in a period of reconciliation. “. . . Reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. In order for that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, an acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour” (TRC, 2015). In this process we acknowledge the land on which we are situated, and we give thankful respect to that land and its peoples. In our acknowledgement, we do not just to pay tribute to the past but acknowledge our collective place and responsibility for the future.

I am going to talk a lot this morning about origin stories, and in doing so, I would like to start with understanding the origin of our place and space here and where we have been for the past few days. For thousands of years, the O’odham, Yavapi, Akimel O’odham, and Hohokam nations have walked gently on the territories where we are based today. I am committed to honouring and respecting the first peoples, and I thank them for their hospitality.

In addition I am going to talk today about communities and collaboration. When I think about communities, I am often drawn to the power of the Indigenous communities in British Columbia. This piece of art, titled “Pulling Together,” was created by the First Nations artist Lou-ann Neel and was inspired by the annual gathering of ocean-going canoes through Tribal Journeys. The art is on the cover of each of BCcampus’ Indigenization Guides, the open professional learning series developed to support the Indigenization of institutions and professional practice. The artwork is intended to represent the connections each of us have to our respective Nations and to one another as we Pull Together.

Working toward our common visions, we move forward in sync so we can continue to build and manifest strong, healthy communities with foundations rooted in our ancient ways. Please keep this in mind as we consider our own origin stories and how we as a community can pull together, working toward our common visions.

I would also like to offer an acknowledgement of thanks to the program committee for the invitation, to be asked to stand among so many mentors, friends, and colleagues. It is an honour to speak in front of all of you today.

Thank you to everyone who has made my family feel so welcome. It is my son’s second open education conference (and he is only seven) and my husband’s first.

Origin Stories

We all arrive here with our origin stories and lived experiences—all of which provide insight into our cultures and our worldviews. My story will provide context for where my thoughts and ideas generate from

This is a picture of me at seven with a traditional Polish costume on.

Truthfully, I have never been comfortable giving my origin story because it always feels hard to explain. It’s far from the norm, and as a child and even as an adult, I longed to belong. I was born in Washington, DC. My father is American and was in the United States Foreign Service, and my mother is Canadian, from Prince Edward Island, was a librarian, a school board trustee, restaurant manager, and took on many other do-er roles. You can probably guess where I get my energy from.

With my father’s role in the Foreign Service, we moved a lot as a family. We lived in England, Poland, Pakistan, Guatemala, the United States, and then I moved to Canada to start university in Nova Scotia. Growing up, I attended schools that had over forty nationalities represented across two hundred students.

My upbringing taught me a few things: to be adaptable, to respect cultural differences, and that there is extreme unfairness, a power to the privileged, in our system. While I may have been living overseas in developing countries, I was also living in large homes, fully furnished with access to drivers, cooks, and people who did our laundry, and I knew that on the other side of the gate to my home and beyond the walls of my international school, lives were not privileged.

We lived in Poland during martial law. A curfew was imposed, the national borders sealed, airports closed, and road access to main cities restricted. Telephone lines were disconnected, mail subject to censorship, and classes in schools and universities suspended.

We lived in Poland during martial law. A curfew was imposed, the national borders sealed, airports closed, and road access to main cities restricted. Telephone lines were disconnected, mail subject to censorship, and classes in schools and universities suspended.

While I was living in Pakistan, less than 39% of Pakistani girls attended high school in urban areas and less than 25% of girls attended high school in rural areas.

While I was living in Pakistan, less than 39% of Pakistani girls attended high school in urban areas and less than 25% of girls attended high school in rural areas.

When it was time to apply for university, my first choice was Union College in Schenectady, New York, but even as a white middle-class student, I couldn’t afford to attend. I was awarded a scholarship that would cover one third of the expenses, but that was not going to alleviate what I saw as a future of financial burden.

I chose to attend Acadia University in Nova Scotia. In 1997 when I started my first year, the institution decided it would have what was known as the first laptop program for students. When you arrived on campus, you were given a student ID card as well as an IBM ThinkPad.

One of the innovative things that Acadia did was hire students to work with faculty to better understand how to use the technology in the classroom and to assist in re-designing courses alongside faculty. I decided to apply to be one of the students to co-create courses and develop materials.

(Looking back, I realize that I was perhaps introduced to open pedagogy at this time.)

I loved being a student instructional designer. The full time employees taught me what I needed to know. They instructed me in what questions to ask, how to be curious, and how interact with faculty to provide suggestions and not criticisms. Because of this experience, I am an extreme advocate for hiring students at our workplaces.

When I graduated, I moved to Calgary, Alberta, and got a job with Mount Royal University as an instructional designer.

My cultural background is the result of many cultures, and while that sounds beautiful and lofty, it is hard. I always wanted to be “from” somewhere, and when we returned to the U.S. when I was sixteen, I felt lost, and my background did not fit in with the traditional suburban teen.

I longed for a sense of belonging.

In 2006, I moved from Calgary, Alberta, to Nairobi, Kenya, to work with the African Virtual University, Open University, and the BBC to create the first repository of open educational resources developed by African educators for African educators. The repository, TESSA (Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa) is for primary-level educators, is available in four languages, and ranges in subject areas from English to life skills to science.

I found my belonging in 2006 when I was introduced to open education in Nairobi, Kenya. I felt welcomed into a newly established community, and I felt that the work I was doing was contributing to a greater cause.

I think many of us have found our sense of belonging through open education. We have witnessed, been a part of, or are currently struggling with the incongruence of the status quo.

And our belonging in this field is a result of our want to do better.

I believe that the purpose of our work—as educators, as policy makers, as system conveners—is to improve access to education, to make education affordable (to the masses and not just the privileged few), and most importantly, to ensure students are successful.

However, the rising cost of post-secondary education is not improving success.

In Canada, 320 undergraduates in B.C. were asked how much they spent on textbooks in the last twelve months. The average was about $700 CAD.

In 2017, in a survey of over 300 students in B.C.,

- 54% said they had not bought a textbook for a course at least once due to cost,

- 27% said they had taken fewer courses,

- 26% said they did not register for a particular course because of the cost of the book(s), and

- 17% said they had dropped or withdrawn from a course (Jhangiani & Jhangiani, 2017).

And textbook costs are far from the only issue. In British Columbia, my colleague Krista Lambert (2017) conducted research on classes that require access to homework systems or digital-publisher resources and found that students pay, on average, $92 per course for an access code.

Similar findings were cited in a 2016 report by the Student Public Interest Research Group (SPIRG). The average cost of an access code sold solo (i.e., not bundled with a textbook) was $100.24.

These “access” codes actually prevent access for students.

Article 26 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN General Assembly, 1948) states that “higher education should be equally accessible to all,” which is impossible when it is for the privileged few.

The late Aaron Swartz was a computer programmer, writer, political organizer, and Internet hacktivist. His passing was a tragedy for the commons. At the age of fourteen, he helped to develop the RSS software that enables the syndication of information over the Internet. At fifteen, he emailed Lawrence Lessig and helped to write the code for Creative Commons. At nineteen, he was a developer of Reddit. In 2011, Swartz was arrested by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) police on state breaking-and-entering charges after connecting a computer to the MIT network in an unmarked and unlocked closet and setting it to download academic journal articles systematically from JSTOR . In his Guerilla Open Access Manifesto paper, Swartz (2008) writes,

Those with access to these resources—students, librarians, scientists—you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out. But you need not—indeed, morally, you cannot—keep this privilege for yourselves.

We need to do better.

The belonging I felt in open education in Kenya then led to me to British Columbia, Canada, where I now lead the open education initiatives across the province. I work for BCcampus, and the organization has been working in open education since 2003. BCcampus serves the entire province of British Columbia, and our role is to work with the twenty-five public post-secondary institutions across the province in the areas of educational technology, teaching and learning, and open education. We’ve been an organization for sixteen years, and we are primarily funded through our Ministry of Advanced Education, Skills & Training, and open education has received additional funding from the Hewlett Foundation.

We are collaborators, innovators, and system conveners.

Our open education work began in 2003 when we started distributing grants to faculty to create and share openly licensed courses. In 2012, our Minister of Advanced Education announced that the province of B.C. would be receiving $1,000,000 CAD to support the development of open textbooks. Since that time, we’ve received another million dollars from the government, we received $250,000 to create the first tuition free and zero textbook cost credential program for Adult Basic Education in North America, and in April of this year, we received $3 million—the largest investment in Canada—toward making education accessible to all students through open education.

When our open textbook project began in 2012, we started with bringing in open textbooks from other collections. We asked faculty to review the textbooks in the collection and incentivized them with $250.00 for each review. As reviews came back, there was a growing trend that indicated that many of the reviewers would use the open textbook if it was changed to include more Canadian examples and be in better alignment with the learning outcomes of their B.C. courses.

We then put a call out for adaptations and using Pressbooks as our publishing tool, we were able to work with faculty across B.C. to adapt some of the open textbooks to meet their needs.

Since the launch of the B.C. Open Textbook Project in 2012, B.C. has saved students more than $14 million, impacted more than 130,000 students, and has a growing open textbook collection of more than 300 books and guides for post-secondary education.

From 2006-2008 when I was working on the TESSA project, I witnessed educators creating content and adapting resources to localize them to ten country contexts. Curriculum in Sudan was translated to Arabic and used geographical examples from Sudan’s landscape. Curriculum in Kenya was adapted for Swahili and English. Science experiments and curriculum outlines were adapted and localized so students and educators could use the materials available to them on the land.

In addition, through collaboration, the post-secondary institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa were printing materials found on the TESSA website and delivering the curriculum to educators in the field via mail.

These institutions were not allowing a lack of an Internet connection to stop them from impacting educators. These institutions saw that their role in furthering the education of students across their country was to ensure that their materials were accessible and that their teachers would be able to impact students regardless of where they live and regardless of their connectivity.

This was the first project that I believe has successfully localized and customized content for students and educators, so that they can see themselves in the curriculum, use the resources available in their context, and read the materials in their language.

How many of your students see themselves and their own origin stories in the curriculum?

How many of your students struggle with instruction that is too disconnected from their own experiences?

Dr. Christina Hendricks of the University of British Columbia conducted research in 2017 titled “The Adoption of an open textbook in a large physics course.” In her survey, she asked students what they liked most about the open textbook.

Their top response? It was customized.

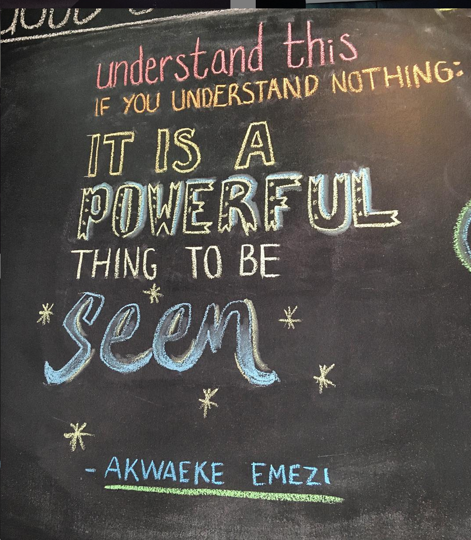

Customization, inclusion, diversity, accessibility, all are under the umbrella of equity, and isn’t that we are trying to do here? Create an equitable environment for our students to be successful?

New America, a nonpartisan nonprofit in Washington, DC, has been writing a blog series to explore the possibilities for creating and implementing inclusive learning materials with a focus on leveraging open educational resources (OER).

In one of her posts, Sabia Prescott (2019) explains that LGBTQ students are never taught material that reflects, represents, or validates their identity and as a consequence, LGBTQ students are less engaged in school, graduate at lower rates, and face much higher rates of mental health conditions than their non-LGBTQ counterparts.

California, New Jersey, and Illinois are now the first three U.S. states to require curricula in public schools to include identities and histories of LGBTQ people and people with disabilities. And here is where the possibility of open textbooks lie for these two states. As Sabia writes,

By openly licensing new textbooks, states could save money and share resources with other education systems across the country, making it easier for schools everywhere to access high-quality, inclusive content. OER also has the power to support content adaptation in ways traditional textbooks do not: With the new legislation, California is updating its history textbooks for the first time in 10 years. The content that goes into these textbooks may very well be used to teach students for another 10 years.

As Jess Mitchell (2019) notes,

If we aren’t designing for inclusion, then we are saying we are comfortable with a certain population of people not being involved.

I am not okay with this.

For the first time it is possible that LGBTQ students will be seen in the curriculum. Imagine if every student, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and more, could see themselves in the curriculum being used.

I shared with you my origin story. It’s time to ask your students theirs.

Katherine Maher, Executive Director of the Wikimedia Foundation, says that the “idea that knowledge should be open and free is a radical challenge.”

Open education is radical in the sense that knowledge should not be the domain of the privileged few. It challenges what comes before and the structures that had been built. And our post-secondary institutions are full of structures.

We are asking institutions to change, and when we ask people to change, we are asking for them to go against their sense of belonging, of what their institutional culture is and has always been.

To best respond to change and orchestrate change in your context, it’s time to ask,

What is the origin story, the cultural background of your institution?

How does it affect decisions made?

Are open values evident in your institutional or school district’s mission or vision?

Community

Our community, the open education community, can often be fraught with misunderstandings and critiques that are fundamentally based on the differing views of our origin stories. For some, the origin story of open education is either based on the open source software movement or a Mormon agenda. But we can actually see the roots of open education dating to the 1960s and 1970s, where by it was a social movement response. In Martin Weller’s book “Battle for Open,” he cites the launch of the Open Universities in the UK as a way to open up education to people who were otherwise excluded because they either lacked the qualifications to enter higher education or their lifestyle and commitments meant they could not commit to full-time education. Open didn’t necessarily mean free, it meant easily accessible to the masses. With the rise of the Internet and the launch of Creative Commons licenses, this was where the opportunity to take the principles of open universities, access to affordable education, and apply an open licence to curriculum to share, remix, revise, and reuse learning materials.

Our community, the open education community, can often be fraught with misunderstandings and critiques that are fundamentally based on the differing views of our origin stories. For some, the origin story of open education is either based on the open source software movement or a Mormon agenda. But we can actually see the roots of open education dating to the 1960s and 1970s, where by it was a social movement response. In Martin Weller’s book “Battle for Open,” he cites the launch of the Open Universities in the UK as a way to open up education to people who were otherwise excluded because they either lacked the qualifications to enter higher education or their lifestyle and commitments meant they could not commit to full-time education. Open didn’t necessarily mean free, it meant easily accessible to the masses. With the rise of the Internet and the launch of Creative Commons licenses, this was where the opportunity to take the principles of open universities, access to affordable education, and apply an open licence to curriculum to share, remix, revise, and reuse learning materials.

In today’s climate, we represent (and rightfully so) the origin story of open education through numbers.

The total student debt in the United States stands at approximately $1.5 trillion (Federal Reserve Bank, 2018).

The Canadian Federal Government is using interest fees on student loans as a source of revenue that was projected to earn approximately $862 million in revenue in 2018 (Vomiero, 2018).

Forty-four million Americans currently owe student loans (Hess, 2018).

The average Arizona state student debt is $33,482 (Kiersz & Malinsky, 2019).

In British Columbia, the student loan debt averages at $28,000 (McIntyre, 2019).

When debt reaches $10,000, student program completion rates drop from 59% to 8% (McElroy, 2005).

According to the Institute for College Access and Success (2018, p. 5), “Bachelor’s degree recipients who were Black, who received Pell Grants, who were the first in their family to attend college, and who attended for-profit colleges were more likely to default on their loans.”

From buying a home to getting married and even having children, an increasing number of young adults are putting off major milestones because of that one large liability.

Audre Lorde, a black, queer poet writes,

Audre Lorde, a black, queer poet writes,

There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.

Student loan debt is not a result of tuition fees alone. It includes books, supplies, tuition, fees, transportation costs, room & board (on-campus), and other living expenses.

When we talk about access and affordability in education, we are talking directly to the effect it has on student success, whether you define success as student completion, improved learning outcomes, or retention.

At BCcampus, communities are at the heart of the work we do.

My colleague Clint Lalonde (2019) wrote a blog post a couple of months ago about the Open Homework Systems project we at BCcampus are working on. He wrote,

Ultimately, for any open education project to succeed and be sustainable, it has to be about developing a community.

At the start of the Open Textbook Project in 2012, we gathered librarians together to create the first open education librarians community in B.C. The B.C. Open Education Librarians is a supportive community to learn about open education practices. Together they seek to build support for librarians and faculty in advocating for the use of OER in their home institution by sharing knowledge and practices that can impact higher education. The librarians who make up this community have worked together to create lib guides across institutions, shared best practices, presented at multiple conferences, and most importantly worked together to ensure that access to educational resources is unencumbered by ownership and cost.

We have also been very focused on building a research community in British Columbia. In 2014 we started the Faculty Fellows program which brings instructors together to engage in research that determines the efficacy of open textbook use in B.C. institutions. The fellows provide mentorship to faculty new to open textbooks through presentations and consultation and conduct outreach activities.

In 2016 my team embarked on an ambitious project: To bring the OpenStax books into Pressbooks so that all of you, the COMMONS, could easily edit, adapt, and customize the high quality OpenStax books to meet the needs of your students. Just this fall, with the support of co-op students and the work of Lauri Aesoph and Josie Gray, there are now thirty-three OpenStax books available in Pressbooks. This work, while beneficial to the B.C. community, has had a profound impact on the entire open education community. When we have the opportunity to make works more accessible in the open community, it benefits us all.

In British Columbia, institutions interested in open education have started open education working groups. These working groups have launched open publishing systems, created open policies, devised grant incentive programs for faculty, hired students to assist in the adaptation of textbooks, hosted workshops and information sessions, and delivered presentations to their institutional community.

Working groups are made up of students, administrators, faculty, librarians, instructional designers, bookstore managers, registrar, I.T. support, and more.

Open education affects and requires stakeholders from all areas of the institution, as each person will have a different lens on how to move open education forward based on their perspective and lived experience with the institutional culture.

We see this outside of British Columbia as well with the Open Textbook Network, which is a vibrant and supportive community that advances the use of open educational resources and practices through member organizations. SPARC’s Open Education Leadership Fellows Program is an intensive professional development program to empower library professionals with the knowledge, skills, and connections to lead successful open education initiatives that benefit students. And in K-12, we have seen communities gather and grow through the #GoOpen initiative, which is a community of state and district leaders collaborating to build knowledge and use OER to transform teaching and learning.

These are high-impact communities that are comprised of people that see the work of others in their network as integral to their ability to achieve impact.

Mary Burgess, BCcampus’ Executive Director, has transformed the meaning of support for a community, specifically when it comes to inclusive practices at our events. For a community to thrive and feel welcomed, each member must feel supported, which is why at our BCcampus events we offer free childcare for parents who seek both professional development and family support, we offer scholarships to instructors and staff who would not otherwise be able to attend due to the lack of professional development funds at their institutions, and if you are a student wishing to attend one of our events, your registration is free. We also have a code of conduct because we are dedicated to providing a harassment-free event experience for everyone.

Gathering a community together can be easy. Ensuring the community feels supported and functions on the realm of possibility and not fear? That is where the work is.

I bring up the origin stories of open education because I believe that each of you has come to this community for reasons based on your own origin story. Your response to access, affordability, content creation, pedagogy, publishing, open source—whether it is because of the technology or social justice—you are here, and that is what matters.

What I am concerned about is that the open education community we have built is divided because we have lost the fundamental goal of why we sit in this room, and that is to enhance student success through accessible education.

Now let’s take a bit of a detour—to IOWA.

In the lead up to the 2006 Democratic Primaries, Dan Pfeiffer, Obama for America National Communications Director, told his team, “If you could win Iowa, then everything was possible.” According to Yohannes Abraham, the Des Moines Field organizer, part of the training was they set expectations like, “Look, we’re going to be down in the national polls. Those don’t matter… Iowa is the key to everything.”

David Plouffee, the National Campaign Manager, said,

From the very moment Barack Obama started talking about [running for] President to the moment he announced, what crystalized was a belief that we needed to win Iowa and that was really our only chance.

Every decision was, ‘How does this help us win Iowa?’

If the answer is that it doesn’t, then we don’t do it.

But what is our IOWA?

I believe that our IOWA, as a community, is to ensure our students are successful in their learning through accessible education.

And if we are going to WIN IOWA—that is, make learning accessible to each student in every classroom—then the only way I see that happening is through open education, open resources, open science, open data, open source, open access….

OPEN.

Collaboration

While community is the noun, collaboration is the verb. For open education initiatives to be sustainable we must collaborate, with each other in this room and with others not in this room. I hope that over the course of the few days you have been able to make connections and identify where collaborations would work to make our community stronger and sustainable.

While community is the noun, collaboration is the verb. For open education initiatives to be sustainable we must collaborate, with each other in this room and with others not in this room. I hope that over the course of the few days you have been able to make connections and identify where collaborations would work to make our community stronger and sustainable.

Based on a decade of research developing detailed case studies on a range of successful networks, Jane Wei-Skillem and Nora Silver (2013) of the University of California-Berkeley identified a common pattern of factors that are essential to effective collaboration. One such pattern that resonated deeply with me is,

“Build constellations rather than lone stars.

Build a larger system to deliver on the mission, not to become the “market leader.”

At BCcampus, our primary focus is to support the post-secondary institutions of British Columbia as they adopt, adapt, and evolve their teaching and learning practices to create a better experience for students. We achieve this through a supportive approach to advanced pedagogies, a focus on impactful practice, and collaboration with partners in B.C. and around the world.

When prepping for this keynote, I asked a few people in the Open Ed community what message would the audience like to hear from me? All said, and I am paraphrasing a bit, how BCcampus has been able to collaborate with so many diverse partners. I believe we have been successful with collaboration because of our core values:

Open. Sharing. Access. Accountability. Quality. Respect.

We have consistently built constellations, not lone stars. We know collaboration is hard, but we see collaboration as a cornerstone of sustainability for the open movement.

I want to share with you a few examples of collaboration and why we have to stop tweaking in silos.

At BCcampus, we have used the sprint model to create both open textbooks and ancillary resources. In 2015, my colleague Clint and I were a part of the first open textbook sprint. We brought together five geography faculty from four institutions for four days to plan and draft a nearly 200-page open textbook for B.C. regional geography.

At BCcampus, we have used the sprint model to create both open textbooks and ancillary resources. In 2015, my colleague Clint and I were a part of the first open textbook sprint. We brought together five geography faculty from four institutions for four days to plan and draft a nearly 200-page open textbook for B.C. regional geography.

Faculty were supported by a librarian, a graphic artist, facilitators, and BCcampus staff, permitting the faculty to focus on their subject-matter expertise.

This effort produced an open textbook that served a local need and which has since been adopted at several B.C. institutions.

A similar approach was taken when several B.C. psychology faculty identified that the absence of a question bank was inhibiting the adoption of a newly-adapted Canadian edition of an open textbook for Introductory Psychology.

In this case, seventeen faculty from six institutions came together for two days to write and peer-review nearly one thousand multiple-choice questions. This resulted in five out of the six institutions adopting the open textbook within a year.

This type of collaboration has also seen success at OpenStax where each year they host a CreatorFest.They bring together the OpenStax user community to collaborate and put knowledge into practice. Instructors develop ancillary resources like test banks, problem sets, and enhanced Powerpoint slides.

This type of collaboration has also seen success at OpenStax where each year they host a CreatorFest.They bring together the OpenStax user community to collaborate and put knowledge into practice. Instructors develop ancillary resources like test banks, problem sets, and enhanced Powerpoint slides.

The sprint model reduces individual workload, results in the production of a higher quality resource and instantly provides inter-institutional credibility of the OER.

In 2014, I worked with Tara Roberston (now at Mozilla, formerly with the Centre for Accessible Post-secondary Education Resources BC or CAPER-BC) and Sue Doner at Camsoun College to create the B.C. Open Textbook Accessibility Toolkit. CAPER-BC provides accessible learning and teaching materials to students and instructors who cannot use conventional print because of disabilities.

In 2014, I worked with Tara Roberston (now at Mozilla, formerly with the Centre for Accessible Post-secondary Education Resources BC or CAPER-BC) and Sue Doner at Camsoun College to create the B.C. Open Textbook Accessibility Toolkit. CAPER-BC provides accessible learning and teaching materials to students and instructors who cannot use conventional print because of disabilities.

The reason for this collaboration was because after creating all of the open textbooks in our collection, the concern was how do we allow our work to be both open and accessible?

We began asking ourselves about true access for all students, including students with visual disabilities. Were we providing a textbook that could in fact be available, be used by the students on day one, and allow them to feel a sense of belonging in the classroom?

At the end of 2014, we contacted the Disability Services Coordinators at partner institutions to find student participants with print disabilities to evaluate B.C. open textbooks. The participants were asked to evaluate five chapters from the open textbook library and provide their evaluation on each chapter.

This worked well, and we decided to take it further and invited the participants to join us for a half-day focus group where we had the opportunity to understand why they responded to the questions—or didn’t respond—to see how they were reading and accessing the materials on their different devices.

Based on student feedback, we were able to make our own textbooks more accessible, and now have an employee, Josie Gray, dedicated to Inclusive and Accessible Design on our Open Education team.

The Rebus Community is an amazing example of collaboration. A dedicated platform for creating and publishing open textbooks. Rebus provides OER projects with publishing guidance, support forums, a Contributor Marketplace, and dedicated discussion spaces. The most recent publication, Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind, had thirty-five collaborators.

The Rebus Community is an amazing example of collaboration. A dedicated platform for creating and publishing open textbooks. Rebus provides OER projects with publishing guidance, support forums, a Contributor Marketplace, and dedicated discussion spaces. The most recent publication, Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind, had thirty-five collaborators.

Collaborations can also happen in ways that may seem counter culture to the open education movement. Collaborations in partnership with for-profit entities such as Lumen Learning or non-profits partnering with for-profits (in the case of OpenStax’s Ally program). And you know what? I believe that is OKAY. It is okay because while they may be using different funding models, they are working towards the same IOWA: to ensure students are successful in their learning through accessible and low-cost education.

Successful collaborations can result in profound policy changes. At UBC, there is now inclusion of language recognizing open in the institution’s tenure and promotion guide (UBC, 2018). OER are now listed as a type of evidence that candidates could present for evaluation, which provides a way for faculty to get formally recognized for engaging in OER activities. This happened because of a collaboration between the teaching and learning centre and the student’s union (AMS of UBC, 2019). This would NEVER have happened without collaboration.

In addition to institutional collaborations, we have also been involved in inter-provincial and global collaborations. In 2012 when the Open Textbook Project was launched, Mary Burgess made it a point to reach out to leaders in the field, those were who were doing the work, testing the waters, and making waves in Open Education. The twenty people gathered at the table represented fourteen different organizations, including OpenStax, USPIRG, Right to Research Coalition, Creative Commons, Lumen Learning, 20 Million Minds, Washington State, and eCampusAlberta. Since that time, we have continued our efforts of collaborating to pay it forward by supporting Pressbooks, sharing publishing best practices with the Open Textbook Network, sharing the B.C. Open Textbook Collection with Manitoba and Ontario, and partnering with Lumen Learning, Open Oregon, and Washington State to host the Cascadia Open Education Summit.

When we collaborate, we invite stakeholders into the process early as a partner, not late as a judge.

While it is true that successful collaborations can be hampered due to challenges (people, communication, and competition), we collaborate because the goal is to improve student learning outcomes, to ensure student success. And we know that alone we can not accomplish this task.

Our greatest resource is the relationships we build in our community through collaboration.

Origin stories matter. Every person has a right to learn and every person has the right to feel a sense of belonging in their classroom and curriculum. Share origin stories, ask others theirs, and ask your students how their origin story is reflected in the curriculum.

We need to ask about our institution’s origin story, its culture, its response to change, which will inform us of how it will respond to the radical challenge of open.

We know the data. We know that student loan debt is debilitating and students face choices that aren’t logical—meals or books?

Open education is the response to the origin story of education as a privileged good.

To make these cultural shifts, I ask that we step back and remind ourselves of why we do this work. How do we achieve our IOWA?

How we move forward has to be through collaboration. Find others working on similar projects, look across institutional structures and across borders.

Be curious. Look for alternative solutions to complex problems. Open education is not a single-issue struggle which means there are multiple strategies to bring to the table.

As I look into the future of education, and in particular open education, systemic and sustainable change is about working together, sharing knowledge, and tweaking outside of our silos. Because together we can achieve success for our students.

Slides: OpenEd19 Keynote – Amanda Coolidge

References

Alma Mater Society of UBC. (2019, February 19). AMS applauds BC government’s decision to reduce student debt [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.ams.ubc.ca/news/ams-applauds-bc-governments-decision-to-reduce-student-debt/

Cellini, S. R., Darolia, R., & Turner, L. (2017, January 6). The government is sanctioning for-profit colleges. What happens to the students? Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/01/06/the-government-is-sanctioning-for-profit-colleges-what-happens-to-the-students/

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Research and Statistics Group. (2018). Quarterly report on household debt and credit [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/hhdc_2018q3.pdf

Hendricks, C., Reinsberg, S. A., & Rieger, G. W. (2017). The adoption of an open textbook in a large physics course: An analysis of cost, outcomes, use, and perceptions. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3006

Hess, A. (2018, February 18). Here’s how much the average student loan borrower owes when they graduate. CNBC. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/15/heres-how-much-the-average-student-loan-borrower-owes-when-they-graduate.html

Institute for College Access and Success. (2018). 13th Annual Report: Student debt and the class of 2017 [PDF]. Retrieved from https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy-files/pub_files/classof2017.pdf

Jhangiani, R.S., & Jhangiani, S. (2017). Investigating the perceptions, use and impact of open textbooks: A survey of post-secondary students in British Columbia. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3012

Kiersz, A, & Malinsky, G. (2019, August 23). Here’s the amount of student debt owed by every US state and DC, in billions. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/student-loan-debt-per-state-2019-4

Lalonde, C. (2019, October 8). Early thoughts on the BCcampus open homework systems project [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://bccampus.ca/2019/10/08/early-thoughts-on-the-bccampus-open-homework-systems-project/

Lambert, K. (2018, October 11). Access code costs continue to burden students [Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://bccampus.ca/2018/10/11/access-code-costs-continue-to-burden-students/

Lorde, A. (n.d.). Quotes from Audre Lorde. Retrieved from: https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/181970-there-is-no-thing-as-a-single-issue-struggle-because-we

McElroy, L. (2005). Student aid and university persistence: Does debt matter? Montreal, QC: Canadian Millennium Scholarship Foundation.

McIntyre, G. (2019, February 19). B.C. Budget 2019: Interest on provincial portion of student loans eliminated. Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/b-c-budget-2019-interest-on-provincial-portion-of-student-loans-eliminated

Mitchell, J. (2019, July 2). ‘Open’ and ‘Inclusive’: How we get both wrong [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@jesshmitchell/open-and-inclusive-how-we-get-both-wrong-1f908a9517c7

Prescott, S. (2019, March 5). What can we learn about inclusive teaching and learning from California and New Jersey? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/what-can-we-learn-about-inclusive-teaching-and-learning-california-and-new-jersey/

SPIRG. (2016). Access denied: The new face of the textbook monopoly [PDF]. Retrieved from https://studentpirgs.org/assets/uploads/archive/sites/student/files/reports/Access%20Denied%20-%20Final%20Report.pdf

Swartz, A. (2008, July). Guerilla open access manifesto [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://openaccessmanifesto.wordpress.com/

Thune, J., & Warner, M. (2019, August 27). Americans are drowning in $1.5 trillion of student loan debt. There’s one easy way congress could help. Time. Retrieved from https://time.com/5662626/student-loans-repayment/

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [PDF], (pp. 6-7). Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

UBC. (2018, July). Guide to reappointment, promotion and tenure procedures at UBC [PDF]. UBC Collective Agreement. Retrieved from www.hr.ubc.ca/faculty-relations/files/SAC-Guide.pdf

UN General Assembly. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights (217 [III] A). Paris. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

Vomiero, J. (2018, May 31). Canadian students owe $28B in government loans, some want feds to stop charging interest. Global News. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/4222534/canadian-student-loans-government-interest/

Wei-Skillern, J., & Silver, N. (2013). Four network principles for collaboration success. The Foundation Review, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.4087/FOUNDATIONREVIEW-D-12-00018.1

Image Attributions

(Listed in order of appearance.)

- “Pulling Together” by Lou-ann Neel. CC BY-NC.

- “Amanda in a traditional Polish costume” by Amanda Coolide. All rights reserved.

- “T-55A on the streets during martial law in Poland” by J. Żołnierkiewicz. Public domain.

- “Amanda and a globe” by Amanda Coolidge. All rights reserved.

- “Attending school in Pakistan” by World Bank Photo Collection. CC BY-NC-ND.

- “Masai School Girl (1)” by GC Communication. CC BY-NC-ND.

- “Aaron Swartz at a Boston Wiki Meetup” by Sage Ross. CC BY-SA.

- “BCcampus website” by BCcampus. CC BY.

- “BCcampus Open Education website” by BCcampus. CC BY.

- “Rumana, a 26-year-old mother in Sudan, went back to school so she could help her own children learn” by Global Partnership for Education – GPE. CC BY-NC-ND.

- “Akwaeke Emezi quote” by Alyson Indrunas. Used with permission.

- “Brussels Is Burning” by M. Sharkey. CC BY-NC.

- “We are open” by cogdogblog. CC0.

- “Audre Lorde” by 350VT. CC BY-NC-SA.

- IMG_1039-FoL18 by BCcampus. CC BY-SA.

- Images of Faculty Fellows by BCcampus. CC BY.

- “College Physics (OpenStax) in Pressbooks notice” by BCcampus. CC BY.

- “Group of people huddling” by Perry Grone. Unspash licence.

- “Mary Burgess” by BCcampus. CC BY.

- “ErgoSum88” [welcome to Iowa sign]. Public domain.

- “Silhouette and stars” by Greg Rakozy. Unsplash licence.

- “BC Booksprint Images” by Clint Lalonde. Used with permission.

- “Sue Doner” by BCcampus. CC BY.

- Accessibility Toolkit – 2nd Edition cover (cropped) by BCcampus. CC BY.

- “Tara Robertson headshot.” Used with permission.