Post by BCcampus Research Fellow Carol Burbee, Northern Lights College (NLC)

As I near the end of my BCcampus Research Fellowship, I note an enduring theme from an earlier blog post. In that post, my co-researcher, Brittney Fouracres, and I shared the FNST 100 curriculum-writing process as a co-constructed path that often invited us to circle back on earlier work. We noticed as we circled back, we took new paths, and the curriculum became richer and more nuanced.

Piloting the coursework in the fall of 2022 supplied an opportunity to consider what it means to circle back pedagogically. One assignment in the course invites students to explore the curriculum and circle back to an earlier discussion and re-engage in conversations that create new paths and a richer, more nuanced experience. As with the curriculum work, to circle back pedagogically amplified new voices and shone a light on stories and perspectives that were missed with the first engagement.

Assignment

“Circle Back and Reflect,” due during week 10 of a 14-week course

Step 1

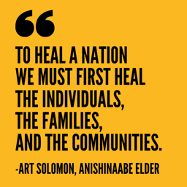

Circle back to your post discussing this quote during week three. Re-read your post and peer responses.

How does this quote speak to you?

Step 2

In your notebook write a response to the following prompt:

“I used to think … Now I think …” (Richart et al., 2011)

Step 3

Find two individuals, not in this class, to collaborate with.

- Ask them how the quote speaks to them.

- Share your original response and your recent response.

- Invite them to share what they notice about your responses.

Step 4

Revise your Step 2 response and post it to the discussion board for week 10.

Step 5

Capture this reflective process and share it with the instructor in Dropbox.

Sample of Student Reflections (Edited for Readability)

“I used to think the healing of a nation should be something that has to be done on an individual level unless it’s not effective. I also mentioned in the week three post that the process of healing a nation is pyramidical in structure, in which the bottom-most is people on an individual level, then families, communities, and finally the nation. But now I think it’s not applicable in all cases, and there might be many possible ways to heal a nation … Now my thoughts are inspired by the healing of the community of Aboriginal Peoples.”

“I used to think healing was a straightforward process that can be achieved easily by just talking and listening to one another and to the families and the community, but after sharing this statement with my friends, I now think healing is more complicated than it seems since we are dealing with human beings. We must dig into the healed wounds that formed scars they are living with. It is difficult to forget a scar when you have it imprinted on you. It is difficult to accept it and live with it without having to remember its cause. Going back to residential schools, we can see the kinds of damage and scars they left on the individuals, families, and communities of Aboriginal Peoples.”

“It was interesting to see how I felt now as opposed to the time before when I wrote it. I feel a lot more passionate about the topic than I did, especially about healing and who is responsible to promote it. I feel it’s complicated, and looking at the trauma of colonialism it isn’t going to be easy or quick. But it got me thinking a lot about the word reconciliation and how it applies to the topic of healing and how colonialism has affected mental health. We are all the nation, but the nation is also the government. I feel that while the government admits its part, its definition of reconciliation may not be a universal fit.”

“Now I think there is more to healing than I thought. As I reflected on the past modules, I realized our nation could achieve recovery, but it would take generations of effort and actions. My earlier post mentioned paying it forward to create a chain reaction. I discussed sharing your healing with as many people as possible in the hopes of helping them process their hurts and achieve the recovery they need. But, as I said, healing is more complicated than that. One of the misconceptions of Canada’s residential school system is that residential schools happened a long time ago. It’s history [living] now.”

“After working with my collaboration people, I believe my statements have gone in a different direction. I used to think this quote was complete and that it was powerful all on its own. But now I am thinking it is incomplete. It is missing part of the process that needs to be acknowledged. Who is ‘responsible for the healing, and who can be a part of that process?’ (personal conversation, Nov. 5, 2022). I have always agreed that the healing process is not linear, and it is messy, but now I am wondering who is allowed to be a part of this process. As Gray (2018) stated, ‘First Nations people do not need anyone to feel sorry for [them],’ but they do need us to ‘understand what [their] issues are, how they evolved, what [their] strengths are, what can be done to foster positive change, and how we all can contribute to that change.’ By understanding what has happened, it will allow us to be a part of the healing process that needs to continue for Indigenous Peoples and our nation.”

The student reflections show how circling back supports depth of understanding and engagement. This assignment is one example of how a decolonizing approach to pedagogy offers new paths, co-constructing the curriculum and inviting richer and more nuanced understanding.

This research is supported by the BCcampus Research Fellows Program, which provides B.C. post-secondary educators and students with funding to conduct small-scale research on teaching and learning and to explore evidence-based teaching practices that focus on student success and learning.

Learn more

- FNST 100 Fall 2022 Reflections – Curriculum Writers: Brittney Fouracres & Carol Burbee [PDF]

- Unsettling Curriculum: A New Course in First Nations Studies 100

- 2021–2022 BCcampus Research Fellows

References

Gray, L. (2018). First Nations 101: Tons of stuff you need to know about First Nations people. Adaawx Publishing.

Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners. Jossey-Bass.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Public domain document. www.trc.ca

© 2022 Carol Burbee released under a CC BY license

The featured image for this post (viewable in the BCcampus News section at the bottom of our homepage) is by Bruno Thethe from Pexels