By Helena Prins, Advisor, Learning + Teaching, BCcampus

The views shared are those of the author and contribute to ongoing conversations at BCcampus about AI, teaching, and learning.

Is it possible to still resist AI in higher education when the train has already left the station?

I have written about the tensions I feel when using GenAI in a previous blog post. And, while I still have so much learning to do, I am not completely anti-AI, but I am anti-inevitability and pro-educational judgment.

One of the reasons I want to continue to support educators in understanding how to use AI appropriately in the classroom is that the resistant-to-AI folks I come across often consider a “No AI” policy announcement in the course outline sufficient, or decide that going back to pen and paper exams will solve all AI-woes. I have difficulty with both these responses as I think our students deserve more. In our BCcampus AI workshops, we often share the AI Assessment Scale (AIAS), encouraging educators to be clear with students about their reasons for allowing AI or for not allowing AI in classrooms and assignments. Transparency and communication about our reasons will not only help students understand but might also build trust instead of resistance. As for the rush back to pen and paper exams, Dr. Ann Gagne articulates the problem with this ableist response much more eloquently than I could in her Accessagogy podcast.

What I deeply hope for is for educator agency in a time of technological overwhelm. As Dr. Neil Fassina, president of Okanagan College, recently stated in a FLO panel, “the speed of AI is evolving much faster than our post-secondary institutions can adapt.” And that’s where we find the tension: while AI has surfaced the need to redefine or clarify the purpose of higher education, educators and students are trying to figure things out in the classroom, without much guidance from administration. Unfortunately, no one seems to know where the pause button is. Refusing to use AI in your classroom often leads to accusations of being resistant to technological change. Surely, there is still a place for pause and careful consideration of the tools that have proliferated in our learning spaces?

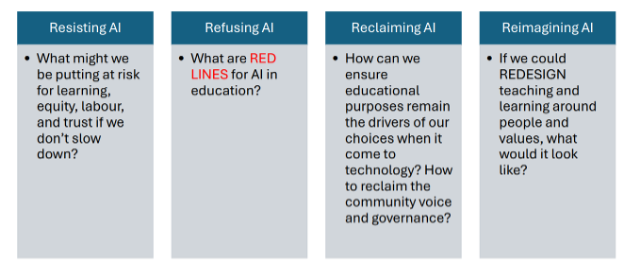

I found Duart et al.’s framework to counter the AI-inevitability narrative helpful in formulating a more productive resistance. Rather than positioning resistance as a single stance or a blanket refusal, Duarte et al.’s framework helped me see resistance as plural, contextual, and deeply practical. It offers four interrelated ways educators can respond to AI without surrendering to inevitability: resisting, refusing, reclaiming, and reimagining. This framework can help us move beyond a binary of adopt versus ban and, instead, it invites us to ask: who decides how technology enters education, and in whose interests is it?

Figure: Four Ways to Counter Narratives of AI Inevitability (from weandai.org)

In this framing, resisting is about pushing back on the narrative that AI must be adopted everywhere and immediately. It asks us to slow down, question urgency, and examine whose interests are being served by rapid adoption. To resist doesn’t mean you are rejecting AI outright, but it means questioning the assumption that adoption is automatic, neutral, or urgent. Resistance shows up when we ask ourselves and those who want us to use AI tools, what problem is this tool actually solving?

Refusing is more targeted and intentional: it is the act of drawing clear boundaries around when, where, and why AI does not belong in a particular course, assignment, or learning context. Here your refusal to use AI in the classroom is not fear-based, but a form of professional judgment (which you, ideally, communicate clearly to your students).

Reclaiming shifts the focus away from tools and back to educational purpose. It invites you, the educator, to reassert what matters in teaching and learning: relationships, process, disciplinary ways of knowing, and human expertise.

Finally, reimagining asks us to consider the question: if we were not constrained by inevitability narratives, what kind of education would we build now? It invites us to imagine learning environments that prepare students to exercise judgment, navigate ethical complexity, and participate critically in a digital world, not necessarily an automated version of education. My colleague, Dr. Gwen Nguyen, created this table to illustrate the questions we can ask ourselves in applying this framework:

So, is it possible to still resist AI in higher education when the train has already left the station? I think it is, but there is a caveat. While Duarte et al. (2025) advocate for the future of AI as a shared decision, I think we might have to let go of the idea that resistance must be collective or absolute. Some educators will choose to board the train; others will not. The more pressing question may be whether we are still allowed to decide. In a landscape shaped by speed, pressure, and inevitability narratives, educator judgment becomes an act of care. Perhaps resistance today is not about stopping the train, but about insisting education remains a relational, contextual practice, and that our students are entitled to more than inevitability.

Reference

Duarte, T., Kherroubi Garcia, I., Anshur, R., Humfress, H., Orchard, D., & Wright, S. (2025) Resisting, Refusing, Reclaiming, Reimagining: Charting Challenges to Narratives of AI Inevitability, We and AI.