A few BCcampus staff members recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Joan Garbutt, Carley McDougall, and Kris Desjarlais, key collaborators on the Pulling Together: Manitoba Foundations Guide (Brandon Edition). We got to hear how they went about adapting the BCcampus Pulling Together: Foundations Guide (the first of the six guides in the Pulling Together Learning Series) into a Manitoba-based resource for Assiniboine Community College and Brandon University staff, faculty, and administration.

Post by Jaime Caldwell, coordinator, Marketing and Communications, BCcampus

Pulling Together Series Background

The Pulling Together guides are the result of the years-long Indigenization Project, a collaboration between BCcampus and the Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training, a steering committee of Indigenous education leaders, and 30 Indigenous and ally authors. The intent behind the guides is to support the systemic change occurring across post-secondary institutions through Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation. The project was supported by the steering committee from B.C. universities, colleges, and institutes; the First Nations Education Steering Committee; the Indigenous Adult and Higher Learning Association; and Métis Nation British Columbia. As the guides were created in B.C., they have many elements specific to local Indigenous groups. For example, Chinook jargon is used throughout as the predominant Indigenous language since it was traditionally used throughout the Pacific Northwest as a trader language. These localized elements make the guides unique but also living, evolving resources that can be adapted and localized in other geographical areas. Collaboration, in this way, knows no borders, no provincial lines.

Turning Passion into Project

Joan, Carley, and Kris all described the way this adaptation began as “stars aligning.” Carley, special projects coordinator at Campus Manitoba, told us her co-worker Kaitlin Schilling was introduced to the Pulling Together series at a conference titled “Educational Impacts in the North,” and when Campus Manitoba later established an anti-racist book club, the Pulling Together: Foundations Guide was the first resource they discussed. Joan, a writing skills specialist at Brandon University, was working with Chris Lagimodiere, then director of the Indigenous Peoples’ Centre, on a special project to undertake while on sabbatical. Chris suggested she make contact with Kris Desjarlais, director of Indigenous Education at Assiniboine Community College, to inquire about any initiatives she could help with. Assiniboine Community College reviewed the Pulling Together guides in 2019 at the urging of their vice-president, Academic, Deanna Rexe. They were looking for a series of resources to adapt and adopt internally within their institution, but things were delayed slightly when COVID-19 hit. So when Joan contacted Kris, he and the Assiniboine team had already reviewed the resources. It was Chris and Kris’s already-established relationships with Elders, knowledge-keepers, and the community that helped lay the groundwork for the project. Recognizing that the guides were open educational resources and curious about the requirements for using and adapting them, Joan reached out to the Teaching and Learning Centre at Brandon University, which referred her to Campus Manitoba. Joan made a cold call to Carley, who instantly recognized (and was already excited about) the Pulling Together: Foundations Guide and the waves it had been making in her own circles. All these individual threads were pulled together, and shared passions collided. The timing was right; the resource was there. A project was born. Then what?

Doing Things in a Good Way

What was at first expected to be a small project quickly snowballed and grew in scope. It is thus very impressive that the project took only nine months from conception to birth. A plan was developed with no official budget as the trio paddled forward, finding ways for each collaborator to contribute with their internal resources. The first step was gauging the comfort level of all involved and finding the best way to work together to launch this worthwhile project. A big challenge was relationship building with various groups in a completely online environment.

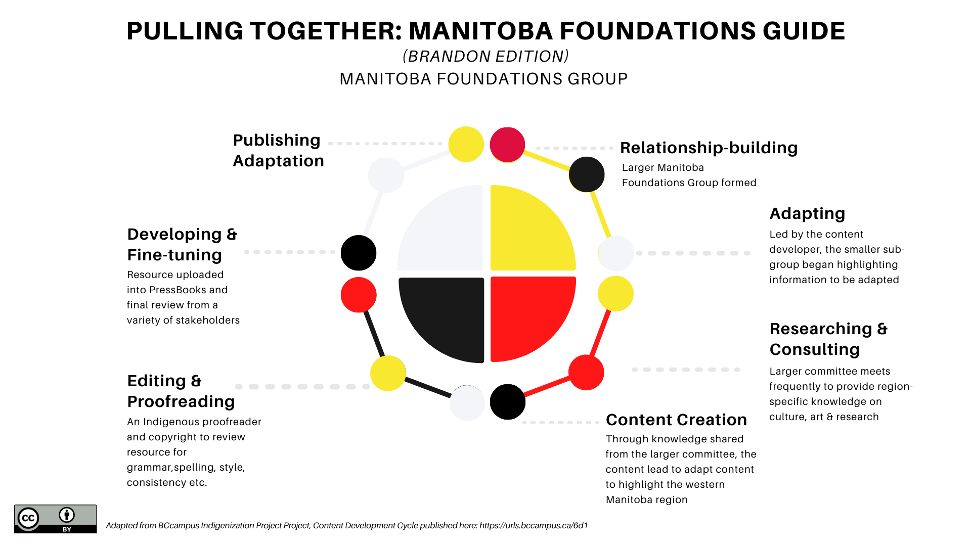

A second challenge was ensuring they adhered to a decolonized approach. In pre-pandemic times, meetings with knowledge-keepers would have been held with specific protocols such as smudging, ceremony, and a sense of grounding. All the work was informed by the knowledge-keepers. The knowledge-keepers on this project were extremely gracious and understood the urgency to make the adaptation a ready and usable guide, as they knew there was a need for it. The colonial project management attitudes were stripped away, and the contributors adopted a cyclical process (see the project development cycle below) where they engaged in ceremony throughout their project. They honoured Indigenous protocols in such ways as taking time to breathe at the beginning of meetings. A focus on actively hearing and listening in the beginning brought a holistic feel to the process. The typical colonial style of formally settling on a specific host and diving right into an agenda in a meeting were put on hold. Those on this project worked in a circle and worked with respect.

One of the guiding phrases the working group used on the project was: “Are we doing this in a good way?” They put an emphasis on leveraging the gifts and skill sets of each person, being iterative through every stage of the project and revisiting things often. People needed, and were given, time to digest and come back to things. “In this project,” Carley said, “both space and grace were created to let things happen.” Ensuring that people had enough time to sit and process was key in this work.

It was essential for this project that all voices be included in the adaptation and that each nation and group see themselves reflected in the guide. While the committee already had the representation of many voices, they reached out to include others when they recognized a gap. The working group sought the knowledge of the Manitoba Inuit and created a significant partnership with the Louis Riel Institute, for example.

Other goals and objectives of this project:

- The resource is adaptable and will continue to be added to and improved on.

- It incorporates languages, symbols, and cultures in this region.

- It can be used and implemented as a tool to expand cultural awareness and diversity.

- It has a holistic approach to awareness of an Indigenous worldview. The team was always mindful of the ways in which Indigenous knowing and being is dismissed. It was more than an academic exercise; the group wanted to encourage people to have a personal reconciliation.

- The ideology behind the context of what is going on and what forms of reconciliation are to happen is important. The group believed that if we want to go forward in a good way, we need to spend time looking back.

- The document should be scalable — a guide used for students but also for managers. However, there could be different levels of self-reflection. Users can scale it to what they expect the outcomes to be. For example, someone could use the guide online by themselves, but the team expects more interaction, sharing circles, and so on with a faculty group engaging in the guide.

- Self-reflection is the most important thing. The team would like a way to continue the process and the learning.

Notable Quotes

“Working on this project has been both humbling and rewarding. I learned more deeply about myself, the importance of relationships, and Indigenous ways of coming together.”

— Carley McDougall

“Non-Indigenous people can (and must!) participate in and be part of reconciliation by recognizing the gifts they can bring to the process, leveraging their privilege in service, and approaching the work with respect.”

— Joan Garbutt

“In a good way is a worldview central to this area of Turtle Island. The final product benefitted from a process-driven approach.”

— Kris Desjarlais

Looking Ahead

What’s next for the Pulling Together: Manitoba Foundations Guide? Getting the word out so this brand-new resource can be put to good use. It is a self-reflective learning tool that can be used in a variety of settings and with different audiences, with the ultimate goal that each reader use the information and knowledge they gain from it to take action toward reconciliation. You can download or read the Pulling Together: Manitoba Foundations Guide (Brandon Edition) here. If you would like a print copy of this guide, contact Kathy Keating <keatingk@campusmanitoba.ca>.

When asked if there will be adaptations of the other five guides in the Pulling Together series, each collaborator expressed interest. The Manitoba adaptation of the Pulling Together: Foundations Guide represents a significant milestone in that it is the first adaptation of this open educational resource, with hopefully many more to come across Canada. The Pulling Together guides were designed to be living resources that can be adapted and localized.

The Manitoba guide and its team of passionate collaborators are examples of the good work that can be accomplished by picking up the paddle and forging ahead in our collective yet very personal journeys toward reconciliation. These resources, intended to augment the existing training currently offered in post-secondary institutions, recognize that place-based Indigenous knowledges, languages, and practices are reflected in the localized delivery of Indigenized learning resources, so they must change as geography changes. However, they work as a template, a starting point, so no one has to begin from scratch, and no one need paddle alone.

You can download or purchase hard copies of any of the guides in the Pulling Together series on the BCcampus Open Text website.

The featured image for this post (viewable in the BCcampus News section at the bottom of our homepage) is by Mark Neal from Pexels