By Fernanda Tomaselli, Assistant Professor of Teaching and Director, Land One program, UBC Faculty of Forestry, and Abhirami Senthilkumaran, Honorary Research Associate, UBC Faculty of Forestry

Board games are increasingly being recognized as powerful educational tools, offering a dynamic way to promote student engagement, foster collective visioning, and support more informed decision-making (Garcia et al., 2022). Unlike traditional lecture-based instruction, board games encourage active participation and deeper involvement in learning. In our BCcampus project, we explored whether playing a collaborative board game focused on climate change could enhance students’ systems thinking competence, influence eco-emotions (such as hope, anxiety, sadness), and increase their sense of agency. Our study took place in a large undergraduate course at the University of British Columbia, involving approximately 200 students. We used an experimental design where half of the participants played Daybreak, a cooperative board game centered on climate change, while the other half played Pandemic, a popular cooperative board game that does not address climate issues. Through this experiment, we gained valuable insights into both the benefits and challenges of using board games in the classroom. While we saw some evidence of enhanced engagement, we also faced a number of practical hurdles. This blog post shares a summary of the key lessons learned that we hope will help educators who are interested in using this innovative pedagogical tool.

We dedicated one week of class time—three hours in total, split across two 1.5-hour sessions—to carry out the study. The first session was used to introduce students to the game mechanics and complete a set of pre-experiment survey questions. During the second session, students played the game and then completed the same survey questions as a post-experiment measure. Participation in the study was voluntary; approximately 120 students took part in the experiment.

The first major challenge we encountered in setting up our experiment was securing suitable classroom spaces to support active learning. Specifically, we needed two rooms that could each accommodate 60 or more students and were equipped with large desks to facilitate group-based, collaborative gameplay. However, most university classrooms are designed for traditional lecture-style teaching and are not well-suited for interactive or hands-on activities. Compounding this issue, the few active learning spaces available were already booked for other courses as our experiment took place mid-term. After several months of searching, we were fortunate to secure two classrooms that met both our spatial and scheduling needs.

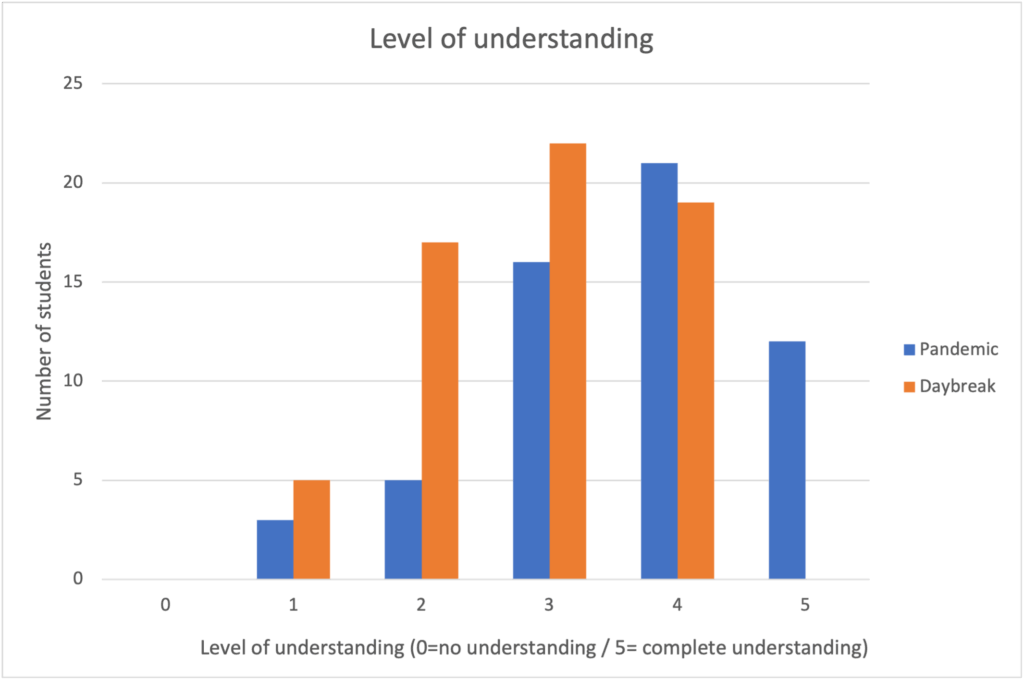

Another challenge we came across was the limited time available for students to learn the games. At our university, undergraduate classes are typically scheduled for a maximum of 1 to 1.5 hours per session. Since we needed to administer pre-experiment surveys and organize students into gameplay groups, the actual time available for learning the game was less than 60 minutes. While Pandemic is relatively straightforward and widely known—nearly 20% of our participants reported having played it before—Daybreak is a more complex game, and very few students were familiar with it. As a result, learning Daybreak within this constrained time frame proved to be a significant challenge. This difference in difficulty was reflected in our post-session surveys where students rated their understanding of the game. As shown in Figure 1, participants reported finding Daybreak harder to understand than Pandemic.

A final major challenge we faced was managing the logistics of facilitating gameplay in a large classroom setting. Our initial plan was to have just one facilitator per session. However, it quickly became clear that students needed much more hands-on support to understand the rules and begin playing, especially given the complexity of the game(s). To address this, we assembled a team of six facilitators (three for each game) who assisted with setting up the games and providing in-the-moment guidance throughout the sessions. These facilitators circulated around the classroom, answering questions and helping groups stay on track. In addition to this in-person support, we created a PowerPoint presentation that outlined the key rules and gameplay mechanics to help students get started more efficiently.

What We Learned: Tips for Educators Using Board Games in the Classroom

After running our experiment, we gained valuable insights into what works—and what doesn’t—when integrating board games into a university classroom setting. Here are some practical tips we hope will be useful for other educators considering this approach:

- Secure an appropriate classroom space well in advance: Board games require physical space and flexibility. Traditional lecture halls often aren’t conducive to group-based, interactive play. Look for classrooms with large tables and enough room to move around, and be sure to book them well in advance.

- Allow ample time for game learning: Don’t underestimate how long it takes for students to learn the rules and mechanics. A one-hour session is typically not enough for students to fully grasp and engage with the game. Aim for longer sessions or multiple class periods if the game is complex.

- Choose the right game for your time frame: Select a game that matches your available time and student familiarity. If your time is limited, opt for a game with simple, intuitive rules. Complex games like Daybreak require more instruction and support, which may not be feasible in every course setting.

- Provide adequate facilitation: Depending on your class size, consider recruiting additional facilitators to support students during gameplay. If that’s not possible, strategically place students who already know the game into different groups to act as peer guides.

- Incorporate assessment of learning: Games can be fun tools to use in the classroom, but it’s important to assess what students are actually learning. We included this learning activity immediately after introducing the unit on the CIMA framework (Causes, Impact, Mitigation, and Adaptation) since those were the game topics most pertinent to the course. Our assessments also focused on evaluating how understanding of these topic areas were augmented by the gameplay activity.

- Be flexible and inclusive: Not all students enjoy games, and some may feel uncomfortable or disengaged. To ensure inclusivity, consider offering an alternative assignment or learning activity for those who prefer not to participate in gameplay. In our case, we offered students the option of watching a climate-related film in a separate classroom.

We would like to thank Sadie Russell, Graduate Academic Assistant, UBC Faculty of Forestry for her excellent work conducting the gameplay sessions.

References

Garcia, C. A., Savilaakso, S., Verburg, R. W., Stoudmann, N., Fernbach, P., Sloman, S. A., … & Waeber, P. O. (2022). Strategy games to improve environmental policymaking. Nature Sustainability, 5(6), 464-471.

Learn More

2024-2025 BCcampus Research Fellows

2024–2025 BCcampus Research Fellows: Fernanda Tomaselli and Abhirami Senthilkumaran