There is a broad literature on open educational resources (OER) in post-secondary education. Most of the existing research has focused on whether students like to save money by using OER (they do!), or whether they perform as well when using OER versus traditional printed textbooks (most studies show that they do). The goal of the project described here is to find out how students use their open texts and what they like and dislike about them. The overall objective is to seek strategies for designing open texts that are better suited to meet the learning needs of students.

Post by Steven Earle, teacher of Earth Science in the Open Learning Division of Thompson Rivers University, Open Education Research Fellow with BCcampus

The study involved 116 students from 9 different B.C. post-secondary institutions—both colleges and universities [1]. Seven different open texts were represented from four different faculty areas: science, social science, arts, and business. Both distance and face-to-face courses were included in the survey.

Students were asked to identify the course they were taking and the OER being used. They were also asked their age range, their self-perceived level of comfort with computers and digital devices, and whether they had used an OER in a class before.

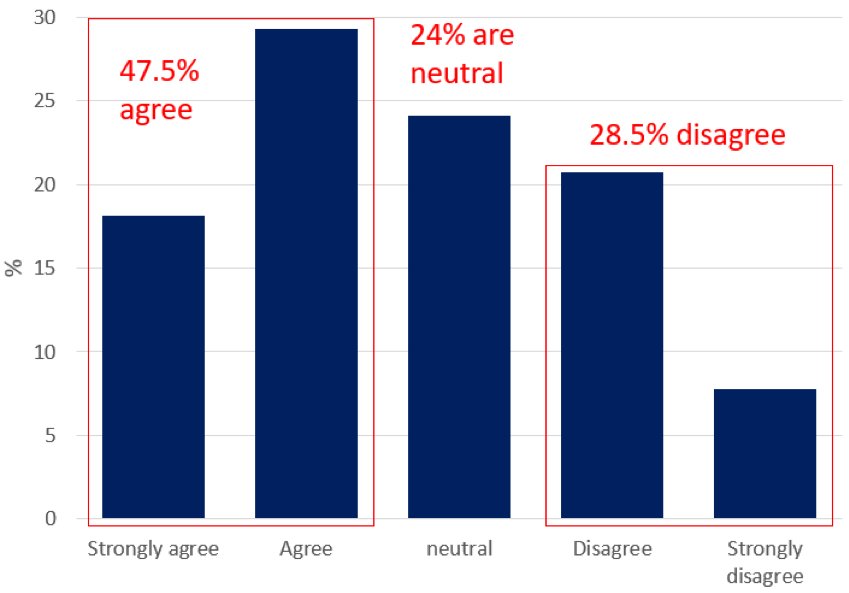

The rest of the survey included a series of multiple-choice and open text questions about the students’ experiences with their OER in a current course. They were first asked how well they agree with the statement: “An online textbook is easier to use than a printed textbook”. As shown in the figure, 47.5% of students agree (or strongly agree) with this statement, 24% are neutral (neither agree nor disagree), and 28.5% disagree (or strongly disagree).

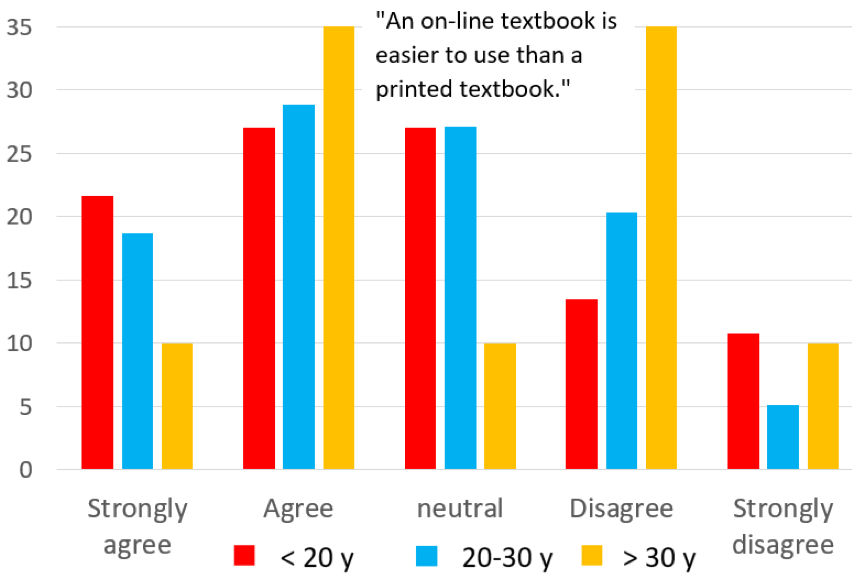

But the numbers are different when broken down by the age of the students. As shown here, 49% of younger students (under 30) agree, while 25% disagree. On the other hand, students over 30 appear to be ambivalent regarding open texts: 45% agree and 45% disagree.

A higher proportion (52%) of students that have some experience with OER tend to agree with that same statement, while fewer (41%) of the first-time users agree. Similarly, 49% of students that are “very comfortable” with digital devices agree, while only 41% of those that are merely “comfortable” agree.

OER are typically available to students in a variety of file formats (PDF, HTML, MOBI, etc.). When asked in what format they most frequently used their text, 58% said PDF and 40% HTML. Only 2% used other formats “most frequently”. While they were not asked the reason for the strong preference for PDF, I suspect that many students like to have their text stored on their device so they can use it when the internet is not available, and they find the PDF format is most suitable for that purpose. When asked in which format they second-most frequently used their text, PDF and HTML were still the top choices, but 22% of students identified other formats that are suitable for portable devices.

Most students (77%) most frequently read their text on a computer, either directly from the text website or from a PDF file. Only 12% most frequently used a phone or tablet, while 11% used a paper copy. Students were also asked how they second-most frequently accessed their text. A phone or a tablet was the second choice for 50% of students, although a significant number (18%) read from a paper copy and the rest still used a computer. Students over 30 tend to have a much greater preference for a paper copy. While 27% of all students printed some or all of their text, 66% of older students did so.

Students who didn’t make or purchase a printed copy of their text indicated various reasons for not doing so. Just over 30% said they prefer to use a digital copy, 36% said they didn’t want to waste paper, and 26% said the cost was too high. On the other hand, when asked if they might have acquired a printed copy under different circumstances, 89% of students implied they might have done so if: “the cost was lower” (42%), “it was more convenient” (36%), they “could have printed selected chapters” (19%), or their “printer was working (or had ink)” (3%).

To summarize, we can see that most younger students are quite positive about OER, especially if they feel very comfortable with digital devices and especially if they have already had experience with an OER in a previous course. In contrast, older students (over 30) tend to be ambivalent with regard to OER.

Students have a strong preference for reading their OER text on a computer from a PDF file, although many also like the freedom to read it anywhere they happen to be, using a mobile device. In contrast, many students — especially the older ones — still like to read from a paper copy and there is some evidence to suggest that more of the students surveyed would have chosen that option if it had been more convenient or less expensive.

I am a strong proponent of OER; I wouldn’t be doing this project if I wasn’t. But it is clear to me not all students love open textbooks. Most students appreciate the significant cost savings and digital convenience, but many have mixed feelings about using them, largely because they struggle with reading from a screen and prefer to read from a paper copy. We need to think carefully, therefore, to ensure that the OER that we create meet the academic needs of students.

1) Most students read from PDF files, so we must ensure that the PDF versions are legible and easy to use. This applies primarily to images and tables. For example, some texts include complex images that are difficult to decipher in a small version, and while students generally have access to a larger version if reading online from an HTML file, that isn’t always the case with a PDF.

2) Most students access their text most of the time on a computer, so it is important to make sure that the design works well for computers. Figures or tables that require the reader to turn the copy by 90 degrees are not easy to read on a computer.

3) If they’re not using a computer, most students access their text on a phone, so we must make sure that the layout is designed to work well for the small screens of phones. This applies to figures and tables especially.

4) Many students still prefer to read a text from a paper copy, so it is critical to make it convenient and affordable for them to do so. It might help if they could choose which chapters to print, and it would be best if the printed copy could be available locally or shipped at a cost that is only a relatively small fraction of the cost of printing.

References:

[1] Thompson Rivers University, University of the Fraser Valley, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, University of British Columbia, Selkirk College, North Island College, Douglas College, University of Victoria, Trinity Western University